Me: "Look, there's a recipe for cookies called Hindus."

E.: "That's not racist or anything."

There's no use sugar coating it. Someone named these cookies "Hindus" because they contain both chocolate and molasses and are, if you will, dark-complexioned cookies.

Oh the hilarity.

The recipe comes from the Rumford Common Sense Cook Book, compiled

by Lily Haxworth Wallace. The 64-page book is undated, but various

folks on the web think that it was published in about 1930. Based in

Rumford, Rhode Island, the Rumford Chemical Works produced the cookbook

in order to promote its Rumford Baking Power.

(The Clabber Girl Corporation continues to make Rumford Baking Powder, although not in Rhode Island.

Before I get a disgruntled note from the Clabber Girl and her legal team, let's make

it clear that there is absolutely no reason to think that the company promotes

racist cookie recipes or endorses any racist uses for baking powder today.)

If this book does in fact date to 1930, it might be that the "Hindus" are reflective of 1920s-era American attitudes towards people from India. Not only was the Indian independence movement in the news, so too was U.S. v. Bhagat Singh Thind, a 1923 Supreme Court decision that excluded Indians from U.S. citizenship due to reasons of race.

Historically, U.S. citizenship had a lot to do with race. The 1790 Naturalization Act limited U.S. citizenship to free, white persons. The Treaty of Guadalupe-Hildalgo not only ended the Mexican-American War, it also declared that Mexicans could be U.S. citizens. That was true even if by the early twentieth century many "Anglos" in the Southwest tried to get around the fact that Mexican-Americans were not just citizens but also legally white. The Fourteenth Amendment rendered Americans of African descent U.S. citizens. The 1870 Naturalization Act allowed African aliens to become citizens. Yet it also opened the possibility that all Asians could be excluded from U.S. citizenship. Later, in 1882, the U.S. Congress barred all but a small segment of the Chinese from entering the United States, and it renewed that restriction in 1892 and 1902. Not until 1943 were Chinese persons allowed to apply for U.S. citizenship.

If you're wondering, Native Americans did not receive full U.S. citizenship rights until 1924.

But if in 1923 blacks, whites, and Mexicans were eligible for U.S. citizenship, and the Chinese ineligible, what did that mean for Asians from places such as India? Were they barred from becoming naturalized citizens?

In 1923, Bhagat Singh Thind, a Punjabi Sikh who lived in Oregon, put that question to a test. He didn't challenge the racism underlying citizenship law. Instead, Thind claimed that he was eligibile for U.S. citizenship because he was, indeed, white. He was white, because he was from Northern India, a region settled by "Aryans." If he was "Aryan," Thind argued, he was white and, therefore, eligible for U.S. citizenship. The Supreme Court disagreed: Asian Indians were neither white nor permitted to become U.S. citizens.

Is it a coincidence that less than a decade after the

Thind decision there appeared a recipe for dark-colored, decidedly non-white cookies called "Hindus"?

I'm not shocked to find that one of my

great-grandmother's old

cookbooks has a racist recipe. What surprises me is that the author

correctly spelled Hindus. You'd think she would have gone with

"Hindoos," which is far more derogatory. It's almost as though she was

trying not to be racist.

Was she? We could also imagine that, while the cookies are racist because they are a play on skin color, they were inspired by the Indian independence movement of the 1920s. Gandhi, a Hindu, gained world-wide fame in the 1920s for his commitment to non-violence and his leadership in the fight to end British rule in India.

These are some very serious cookies.

But not everything in the 1920s was so sternly different from today. The Rumford Common Sense Cook Book contains other, humorous, non-racist gems. For example, it would be a terrible shame if I fail to make the Corn Flake Cookies.

Then there is the fantastic advice on school lunches. What kid wouldn't want mashed baked beans with mayonnaise or chili sauce? Of course, I used to eat

chow mein sandwiches, so what do I know? I certainly was unaware that: "Boys like plain folding lunch boxes, girls prefer daintiness of equipment."

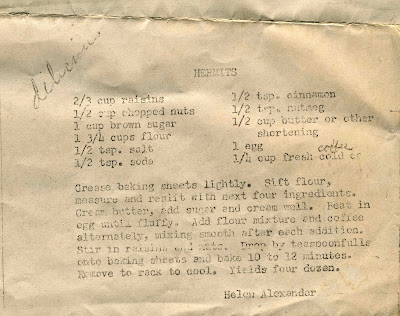

Feel free to study this page yourselves.

For the record, I assume that the Spanish Meat Loaf is racism-free. It contains pimientos, which are Spanish. That one's legit. Although, only someone lacking common sense would ask for this meatloaf in Spain.

Even if these recipes are probably not something you'd likely Google in preparation for your next meal, they might be worth trying. The "Hindus" were delicious. No, they were the best

cookies I've ever made.

The batter was light and fluffy. Forget about baking, I could have served it in a tall glass and called it dessert. It was like a fine mousse. So, seeing as I'm not going to serve "Hindus" to my friends, I've decided to change the name from "Hindus" to Mousse Melts.

E. agreed with me. "That's far less racist," he said.

Less? I was going for not racist at all.