Showing posts with label Great Depression. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Great Depression. Show all posts

Tuesday, April 17, 2012

Brownies

Among the family recipes that I have gathered is one for brownies included in a note written to my Great-Aunt Barbara.

46 Oak Street

Taunton, Mass.

June 24th

Dear Barbara -

Congratulations and all that sort of thing! I hope you will have the best of summers.

I can not thank you for being such a trump the day of the fashion show! Please let this "baseline" help me.

Sincerely,

Martha Foster

(over)

Baseline? Maybe that's a play on baste line? Fashion show humor. You had to be there. (Or maybe someone out there can transcribe that line better than I did.)

Thanks to good ol' retro-stalker (ancestry.com), I was able to determine that Martha Foster lived at 46 Oak Street in 1933 and 1934, when Barbara was fifteen or sixteen years old. Born in New Hampshire in 1902, Martha Foster worked as a teacher at Taunton High School. In 1938 she married her colleague, Walter Bowman, and thereafter she was known as Martha F. Bowman. The couple lived in Taunton and finally settled in or near Mattapoisett, Massachusetts.

I doubt that Barbara and Martha were close friends. Martha Foster was born about 16 years before my great-aunt. Barbara attended St. Mary's, not Taunton High, so it's unlikely that the two had a student-teacher relationship either. Nevertheless, even as a teenager Barbara was probably a godsend at a fashion show. She was always at her sewing machine.

It's just a nice little thank-you note and someone in the family probably saved it for the sake of keeping the recipe. Maybe Martha's brownies were the culinary hit of the show, and Barbara just had to make them herself. My great-aunt was a wonderful cook.

Well, the fashion show may be long over, but we can still judge the recipe. The brownies are chewy and moist and not too difficult to make. They're a little sweet though. Maybe baking chocolate has a bit more sugar now.

You'll need a small pan. Keep in mind that it was the 1930s. Waste not, want not and all that sort of thing.

Wednesday, February 29, 2012

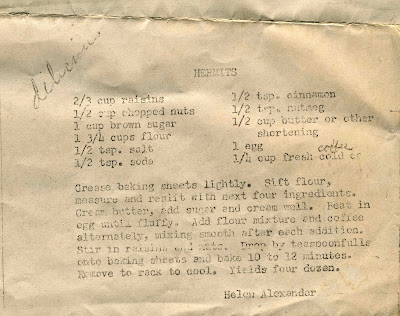

Hermits

I grew up eating hermits all the time, because my father really likes them. No one else I knew ever ate these spiced raisin cookies though. They're still around, but they are by no means something that I see everyday. This recipe was one of the many my great-aunt collected or received from friends. Perhaps a friend named Helen Alexander gave it to her.

I grew up eating hermits all the time, because my father really likes them. No one else I knew ever ate these spiced raisin cookies though. They're still around, but they are by no means something that I see everyday. This recipe was one of the many my great-aunt collected or received from friends. Perhaps a friend named Helen Alexander gave it to her.

They're simple treats, and yet it seems that no one really has them figured out. Many believe that hermits probably originated in the New England region. One interested blogger out of Boston named Lady Gouda thinks of them as bars rather than as cookies. I can see that. Another notes that they were especially popular during the Great Depression. That makes sense, since molasses would have been cheaper than sugar.

My father didn't grow up during the Depression, but both of his parents served as social workers helping people to make it through that hard time in the city of Fall River, Massachusetts. I may not know where hermits come from exactly, but I do know that my grandfather introduced them to my father.

Or maybe their living in New England predisposed them to this molasses cookie. According to the authors of America's Founding Food: The Story of New England Cooking, beginning in the late nineteenth century and continuing through the first decades of the twentieth century, New England cooks overwhelming preferred molasses to sugar regardless of costs. Sensing that Yankee identity and New England's influence in the nation were waning, female cooks and cookbook writers looked to molasses and its historical ties to New England as a means to managing the blows to their identity. Perhaps molasses helped to foster the popularity of hermits in region.

I guess the Yankee identity crisis had subsided by the time my great aunt received this recipe, because it does not contain molasses. The hermits that my father and I have enjoyed were much darker in color than than the ones that I made from my great aunt's recipe. That's probably due to the lack of molasses and to the fact that I only had light brown sugar on hand.

Most recipes for hermits require molasses, and some, but not all, list brown sugar as an ingredient. So, this recipe is unique or unusual in that it calls only for brown sugar. Coffee is also not a standard ingredient, but there are many hermits recipes out there, including one that claims to be Pennsylvania Dutch in origin, that use coffee.

New England. Pennsylvania. No one knows where these simple, little cookies or bars began.

Nevertheless, the person who penned "delicious" on the recipe before putting it through the ditto machine was right. These hermits are really good. They may not have molasses, but even with the first bite there was no mistaking Helen Alexander's recipe for anything other than hermits.

And who was Helen Alexander? Well, what I know about her makes my knowledge of hermits look encyclopedic.

Sunday, November 29, 2009

The Great Chow Mein Famine of ‘09

When I was a student at South School in Somerset, Massachusetts, we engaged in a daily ritual that we imagined common to children across the United States. In the lunch line, we placed on our trays a plastic knife and spork, a carton of coffee milk, a giant sticky roll for dessert and, if we were lucky, a chow mein sandwich.

The woman working the line would give you a styrofoam tray with distinct sections (only on chow-mein-sandwich day were we treated to styrofoam) filled with brown sauce, two slices of white bread, and a brown wax-paper bag full of crispy fried noodles.

Chow-mein-sandwich day was the most important day of the week. I preferred to axe the gravy and the white bread and just eat the noodles out of the bag. But I can still remember the grin on the face of one of my classmates, a sweet kid named Tony who spoke English with a slight Portuguese accent, as he gently rushed his chow mein sandwich to his seat in the cafegymatorium.

What chicken tikka masala is to London or bagels are to New York City, the chow mein sandwich is to greater Fall River.

Yet for much of 2009 the world, or the world that is southeastern Massachusetts and Rhode Island, has been deprived of chow mein sandwiches.

In June fire struck the Oriental Chow Mein Company, founded by Frederick Wong. For decades, this Fall River business has supplied local schools, restaurants, and stores with its distinctive, crunchy chow mein noodles. As of mid November the Wong family, which still owns the company, was trying to re-open at the same time that it warded off incessant phone calls with demands for noodles. Since the 1930s the sandwich has been listed on the menus of both Chinese and American restaurants and the Oriental Chow Mein Company has been and remains the region’s sole noodle distributor.

Could chow mein sandwiches become a bygone food?

If you have missed Emeril Lagasse’s expressions of love for chow mein sandwiches or did not grow up with him in Fall River, you might not know what a chow mein sandwich looks like or how to make one yourself. It’s not pretty, but it is tasty. Basically, it consists of crispy fried noodles covered in a brown sauce, which likely contains pork and only sometimes celery and other vegetables, placed on a hamburger roll or between two slices of square white bread. You may order it unstrained, with celery and other vegetables, or strained, without celery and other vegetables.

You can also, or once could, make it at home with the packaged version that the Oriental Chow Mein Company has distributed to grocery stores. Coveted boxes of Hoo-Mee Chow Mein are rumored to be selling for upwards of fifty dollars each since the fire.

You can also, or once could, make it at home with the packaged version that the Oriental Chow Mein Company has distributed to grocery stores. Coveted boxes of Hoo-Mee Chow Mein are rumored to be selling for upwards of fifty dollars each since the fire.

The box, while reproduced until recently, is obviously of an earlier era; it contains a message explaining that Hoo-Mee Chow Mein is best made by housewives. Perhaps this marketing strategy helped to bring what was once an “exotic” food served outside the home into local kitchens.

But why chow mein sandwiches and why Fall River?

Fall River was once booming with textile factories and immigrants from Ireland, England, and Quebec to fill them. The story goes that chow mein sandwiches took off during the Great Depression of the 1930s, because a sandwich was cheaper to buy than a full portion of chow mein. Order a sandwich and you purchased less chow mein, but you at least had the bread to fill you.

The Depression hit Fall River hard and it never really recovered. I do not know if it can withstand the loss of chow mein sandwiches.

The chow mein sandwiches made possible by the Oriental Chow Mein Company are a testament to southeastern Massachusetts’ unique population and immigration history. Chinese-immigrant cooks, no matter where they settled, tailored their foods to the pre-existing culinary propensities of customers. The brown sauce of the chow mein sandwich reflects the tastes of Fall River’s established Yankee, Irish, and English populations of the 1920s and 1930s. The sauce and its contents are cooked for a long period of time or boiled, producing soft vegetables. Given the popularity of boiled foods in New England and among British and Irish immigrants, especially in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Chinese-American cooks like those in the Wong family probably tailored the sauce to their expectations. This, I venture, helps to explain why the soupy sandwich took off in Fall River in particular.

It remains beloved by many, including those of French-Canadian descent.

I would love to know what exactly happened when someone first asked a Chinese-American cook (Frederick Wong?) for a chow mein sandwich. Or did the cook take the initiative in first offering it to customers?

Most of all, I wonder, was that moment strained or unstrained?

The woman working the line would give you a styrofoam tray with distinct sections (only on chow-mein-sandwich day were we treated to styrofoam) filled with brown sauce, two slices of white bread, and a brown wax-paper bag full of crispy fried noodles.

Chow-mein-sandwich day was the most important day of the week. I preferred to axe the gravy and the white bread and just eat the noodles out of the bag. But I can still remember the grin on the face of one of my classmates, a sweet kid named Tony who spoke English with a slight Portuguese accent, as he gently rushed his chow mein sandwich to his seat in the cafegymatorium.

What chicken tikka masala is to London or bagels are to New York City, the chow mein sandwich is to greater Fall River.

Yet for much of 2009 the world, or the world that is southeastern Massachusetts and Rhode Island, has been deprived of chow mein sandwiches.

In June fire struck the Oriental Chow Mein Company, founded by Frederick Wong. For decades, this Fall River business has supplied local schools, restaurants, and stores with its distinctive, crunchy chow mein noodles. As of mid November the Wong family, which still owns the company, was trying to re-open at the same time that it warded off incessant phone calls with demands for noodles. Since the 1930s the sandwich has been listed on the menus of both Chinese and American restaurants and the Oriental Chow Mein Company has been and remains the region’s sole noodle distributor.

Could chow mein sandwiches become a bygone food?

If you have missed Emeril Lagasse’s expressions of love for chow mein sandwiches or did not grow up with him in Fall River, you might not know what a chow mein sandwich looks like or how to make one yourself. It’s not pretty, but it is tasty. Basically, it consists of crispy fried noodles covered in a brown sauce, which likely contains pork and only sometimes celery and other vegetables, placed on a hamburger roll or between two slices of square white bread. You may order it unstrained, with celery and other vegetables, or strained, without celery and other vegetables.

You can also, or once could, make it at home with the packaged version that the Oriental Chow Mein Company has distributed to grocery stores. Coveted boxes of Hoo-Mee Chow Mein are rumored to be selling for upwards of fifty dollars each since the fire.

You can also, or once could, make it at home with the packaged version that the Oriental Chow Mein Company has distributed to grocery stores. Coveted boxes of Hoo-Mee Chow Mein are rumored to be selling for upwards of fifty dollars each since the fire.

The box, while reproduced until recently, is obviously of an earlier era; it contains a message explaining that Hoo-Mee Chow Mein is best made by housewives. Perhaps this marketing strategy helped to bring what was once an “exotic” food served outside the home into local kitchens.

But why chow mein sandwiches and why Fall River?

Fall River was once booming with textile factories and immigrants from Ireland, England, and Quebec to fill them. The story goes that chow mein sandwiches took off during the Great Depression of the 1930s, because a sandwich was cheaper to buy than a full portion of chow mein. Order a sandwich and you purchased less chow mein, but you at least had the bread to fill you.

The Depression hit Fall River hard and it never really recovered. I do not know if it can withstand the loss of chow mein sandwiches.

The chow mein sandwiches made possible by the Oriental Chow Mein Company are a testament to southeastern Massachusetts’ unique population and immigration history. Chinese-immigrant cooks, no matter where they settled, tailored their foods to the pre-existing culinary propensities of customers. The brown sauce of the chow mein sandwich reflects the tastes of Fall River’s established Yankee, Irish, and English populations of the 1920s and 1930s. The sauce and its contents are cooked for a long period of time or boiled, producing soft vegetables. Given the popularity of boiled foods in New England and among British and Irish immigrants, especially in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Chinese-American cooks like those in the Wong family probably tailored the sauce to their expectations. This, I venture, helps to explain why the soupy sandwich took off in Fall River in particular.

It remains beloved by many, including those of French-Canadian descent.

I would love to know what exactly happened when someone first asked a Chinese-American cook (Frederick Wong?) for a chow mein sandwich. Or did the cook take the initiative in first offering it to customers?

Most of all, I wonder, was that moment strained or unstrained?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)